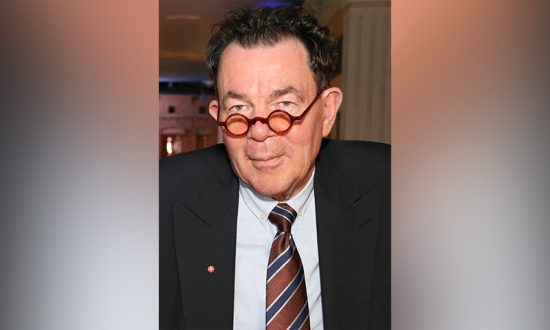

Professor Dr Ger Graus OBE is a renowned figure in the field of education. He was KidZania’s first Global Education Director and founding CEO of the Children’s University. In 2019, Ger became a Visiting Professor at the National Research University, Moscow, Russia. He is also a Board Director at Hello Genius, and chairs the Advisory Boards at Kabuni, UK, and Twin Science, Turkey. Ger moved to the United Kingdom in 1983 where he began his teaching career, later becoming a Senior Inspector, and Education Director. Dr Graus is a member of Bett’s Global Education Council; DIDAC India’s Advisory Board; Junior Achievement’s Worldwide Global Council; chairs the Beaconhouse School System’s Advisory Board, Pakistan; advises the Fondazione Reggio Children, Italy, and the International Schools Partnership (ISP); and has been invited to help shape the future of education in Dubai as a member of the Dubai Future Councils.

According to you, how has education changed over the years? Do you think it has changed for the better?

Not with the times, and no not really. Let me paint a picture that could and should be much prettier.

First and foremost, let us distinguish between ‘schooling’ and ‘education’ – 9 to 5, 192 days per year, versus always. Driven by governments, schooling has narrowed; a narrower curriculum, only valuing what we can measure, less and less relevant to the goings-on in the real world, providing less and less purpose. Children and young people are numbers, stuck in the supply and demand model of the first and second industrial revolutions and all that followed. Teachers are not respected when they should be. We live in a world of hype over substance. Secondly, the same applies across the piece: from early years to higher education.

Education opportunities on the other hand are greater, better, cheaper, more accessible, and increasingly relevant to the individual rather than the masses. Not bad. Enhancements in technology, how we access, and ever more adventurous content will add to this with increasing speed.

So why are we not trying harder to bridge the gap between what can be taught in school and what can be experienced and learned out there? What are we afraid of? Breaking a mould that is long broken?

In terms of educational opportunities and bridging the gap between theory and experience, governments can get in the way; for example, Brexit means that United Kingdom university students can now no longer access the Erasmus Programme. Governments can also be of great support; for example, in the roll out of accessible high quality internet infrastructures in the Netherlands, Switzerland, most of Scandinavia, South Korea and Japan. Have internet, will travel!

We are experiencing a loss of purpose, too many “I don’t know why I’m doing this” moments. And a loss of trust; politicians do not trust teachers – hence inspection regimes that do not make a difference to the life chances of children, and, sadly, teachers at times do not trust the children and young people as much as they should. Parents seem to trust no one, and often think they know best – which they mostly do not. Our aspirations are greater for more, but not for all. Children and young people can still only aspire to what they know exist. The curriculum is largely irrelevant to the needs of our society. The many, many children and young people who are successful in their schooling all too often do not know what to do next. That bit is broken unless you can afford a private education for your child, with all the trimmings. The gap between rich and poor is increasing. In the sixth largest economy in the world children still come to school hungry. It is not all Maths and English you know.

We know more and we are better at recognising the issues but not that much better at addressing them. Too much is out of the control of those who know best, our headteachers and senior leaders. Our teachers are better and work harder than ever but are swimming against an increasingly strong tide.

Imagine if we had a shared sense of relevance and purpose, each knowing which roles to play and were led by the experts; trust would have to follow, and we would have a world where “every child is everyone’s responsibility” ( Vanessa Langley – Headteacher, Arbourthorne Community Primary School, Sheffield, United Kingdom), where everyone is an educator and everyone is both a role model and scaffolding to a child. It is not rocket science.

Incidentally, I tend to use the words children and young people more than any others, because they are easier and better than pupil, learner, student or whatever; it is about who, not what, they are; it is about the person specification, not the job description.

With technology on a rampant path in education. There is always a need for teachers to stay updated with the times. In a time like this, what are a few simple methods that teachers can adopt to better their teaching? How can they use tech as a benefit?

As a tool to enhance learning at its very best. In schools, children and young people will be able to see everything, experience most things, and in time become confident, independent, curious learners, wishing for more. Look at the opportunities offered by technology in the form of Hello Genius, Kabuni or Twin Science, to name, from personal experience, but a very few.

But, we may have to reevaluate the role of the teacher. Of course, teachers need professional development, continually, like doctors. But, to do what? Who is the teacher? The teacher as the purveyor of knowledge, the project manager of children’s learning, or both? With new technical support roles aiding them, and these could be older learners who are remunerated. My 17-year-old daughter for example knows more about technology than most; why not pay her to do a job, in her school, thus allowing the teacher to focus on the children, their learning, wellbeing, and the awe and wonder? What about parents, carers, the world of work, the third sector, communities, other schools as educators serving the context in which children find themselves? How about future pathways education for 6-year-olds with the support of the community, the world of work, higher education as educators, some of it on- and some off-line? [Keep an eye on my work with the Independent Schools Partnership.] Work experience for 8-year-olds to widen horizons and provide a sense of purpose? Virtual visits to the Guernica at the Museo Reina Sofia accompanied by a local artist in residence? Why on earth not? But, give teachers a break, and a give them helping hand.

The answer is also that learning, all learning at all ages, is a jigsaw of partnerships; find the right partnerships and see a better and bigger picture.

We really need to rethink all this and make courageous decisions. For the sake of our children and young people.

Though tech has become part and parcel of our lives today, there are disadvantages as well. When it comes to education, how do we strike a balance with students in the process of learning?

By religiously focusing on the two key aspects: the children and young people, and the learning. The rest is secondary, and common sense.

Technology is there to serve, and it is important to distinguish between ‘good tech’ and ‘tech for good’. The focus sadly is still too much on ‘good tech’, technology that is shiny and promises the world. ‘Tech for good’ is technology to make the learning better, faster, more exciting, full of awe and wonder, endless; it has purpose.

We also have yet to define new methodologies properly, e.g., hybrid learning, where we float seamlessly between environments, be they on- or off-line. Hybrid learning is still too much like hybrid cars: either-or, with a constant worry that we might run out of gas.

And, finally, we must remember where Covid-19 shone a light: unless in educational terms we see access to technology and its infrastructure as a global educational entitlement – like, in health terms, access to clean water, we will aid in the widening of the gaps between have and have-not and can and can-not.

How did you gain that entrepreneurial spirit to establish the Children’s University? What was your motivation?

From experience. Prior to the Children’s University, my role as Director of the two Wythenshawe Education Action Zones (WyEAZs) in South Manchester in the early 2000s taught me that private-public sector partnerships work, not in the conventional sense but in a win-win scenario. By the way, Wythenshawe is now also known as Marcus-Rashford-land!

Education Action Zones were an initiative under Tony Blair’s government which focused on areas of severe socio-economic disadvantage in partnership with the private sector, in my case Manchester Airport Plc. The aim was to raise the bar in communities, and with communities, including the business world. We had, by law, the right to do things differently in order to make things better; more of the same would have just fed the definition of insanity: keep doing the same thing and expect different outcomes.

To all intends and purposes, this set-up behaved like a social enterprise company: not for profit, with the heart of a charity, and the head of a business. It seemed common sense to take this approach into the Children’s University and contextually adapt it. It worked, and it worked globally.

Clearly, you are a global citizen. With numerous involvements in different organisations and continents, do you believe in the philosophy of ‘One Size Fits All’?

No. Categorically. Each child, each young person is unique, a citizen, competent and a holder of rights.

I have never understood the ‘one size fits all’ terminology. We do not apply it in everyday life, in fashion for example, or cars, or television screens; even in economy class on flights there are aisle and window seats, or those with more legroom. Our world pretty much recognises that we are all more or less different – except, seemingly, in the debate we have around schooling. So, I will just leave that there.

What part of education do you think needs improvement? How can it be implemented?

Firstly, all of it and all of the time. We have to agree not to stand still, because our children and young people, and their lives do not.

We must also agree that we need to focus on the learner before anything else. We need to shift our accountability from serving the system to serving the child and the young person and their potentials. We need to trust the children as much as they trust us. A child is not a citizen of the future but of the here and now. In a society where everyone will be a lifelong entrepreneur of some kind, schooling and education can no longer be a mass production affair; that served the first and second industrial revolutions and all that followed, as was so aptly described by the Scottish comedian Sir Billy Connolly: “At 14, the schools opened their doors and the shipyards, at the same time, opened theirs. I joined the wrong queue and became a welder.”

We suffer from a lack of preparation and preparedness for the next phase of schooling. Every time, all the way from kindergarten through to university and beyond. Ours is an educational pass-the-parcel culture where child is a product. Schooling is not a smooth journey; it is a bus ride with many stops and starts.

Finally, we should start early. I have never understood why there is so little focus, including resources, on early years. In schooling terms, we invest more the older the learners become. Who in their right mind, when building a house starts with the roof? We urgently need to turn our thinking upside down, so that we can start with the best possible foundation on which to build our children’s lives. We need them to enjoy the fact that in life there are no straight lines and be competent to cope with unexpected items in the bagging are of life. Skills start early!

As a professor, you have experience in research and learning. If you had to choose what in your opinion is the most important part of research?

It’s focus. Is the research conducted and published with a view, however broad, to make the world a better place? Do its outcomes encourage positive activism? Education research needs us to be able to reimagine and action a better childhood and all that follows, time and time again.

Share one tip with us for students entering the field of education. What do they need to prepare themselves for?

A quote from my favourite book, ‘The Little Prince’ by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: “All grown-ups were once children, but only few of them remember it”. Remind yourself what it is was like to be the same age as the children and young people you are with, get to know them and then stand in their shoes. Empathy will allow you to plan and execute your teaching to the individual children and young people in front of you. It will allow you to become the role models they need. Do what most governments do not do: care deeply. Then let your passion become your purpose.

What does the future of education look like to you?

Rosy. With and without my glasses. When it comes to the education of our children and young people, we should only be allowed to be optimistic. There can be no other way. Hope, optimism, and their realisation are our collective responsibility. As educators and teachers, that is what we do.

All futures will always have schools that are ‘more than a school’, in communities that care, with wonderful teachers and educators who go the extra mile, and children at the centre. Much of the rest is about context and circumstances and often out of the direct control of the schools and their leaders: finances, resources, support services, infrastructure, technology, et cetera.

I would like to see a future where schooling and education are depoliticised, where experts are the leaders and decision makers, and where private-public partnerships work under the umbrella of ‘return on involvement’ as opposed to ‘return on investment’, for the benefit of the children and young people, and their futures.

The awe and wonder of learning will always be there as long as we have wonderful teachers and educators. I hope we will see in future recognition and greater respect for the professions and that ‘Tr’ for teacher becomes the equivalent of ‘Dr’ for doctor.

Who, in your personal opinion, has been an inspiration to you and why?

There are many, personally and professionally, from my family of course and friends to colleagues and fellow professionals.

Professionally, the person who stands out for me is Professor Carla Rinaldi, President of the Fondazione Reggio Children. Carla Rinaldi’s thinking about children from the earliest of ages, their families, and communities, their education, including schooling, stands as an example to all of us. Her emphasis on learning is beyond boundaries of any kind; her research and analysis are peerless. She is in my view one of the most important educational philosophers since the 1950s. She is also one of my absolute best and very dearest personal friends!