Mark joined Studyportals as the Senior Partnerships Director for the UK & Ireland in July 2022 and is primarily responsible for connecting with top universities to help them diversify and grow their international student body, as well as providing them with challenging insights on international student mobility and ways to grow quality and retention of their international cohort. Mark has been working in International HE since 2011, starting at QAHE in Birmingham where he was an international officer for Africa and spent time traveling around the continent to recruit students to come and study in the UK. In 2014 he relocated to Portsmouth to look after their interests in the MENA region and then from 2017-2022 he ran the large global recruitment, marketing, and admissions teams for the University of Portsmouth, managing all pre-arrival activity for international students. He has substantial experience in both the public and private domain of the UK Higher Education sector- allowing him to understand key dynamics from multiple perspectives.

Introduction

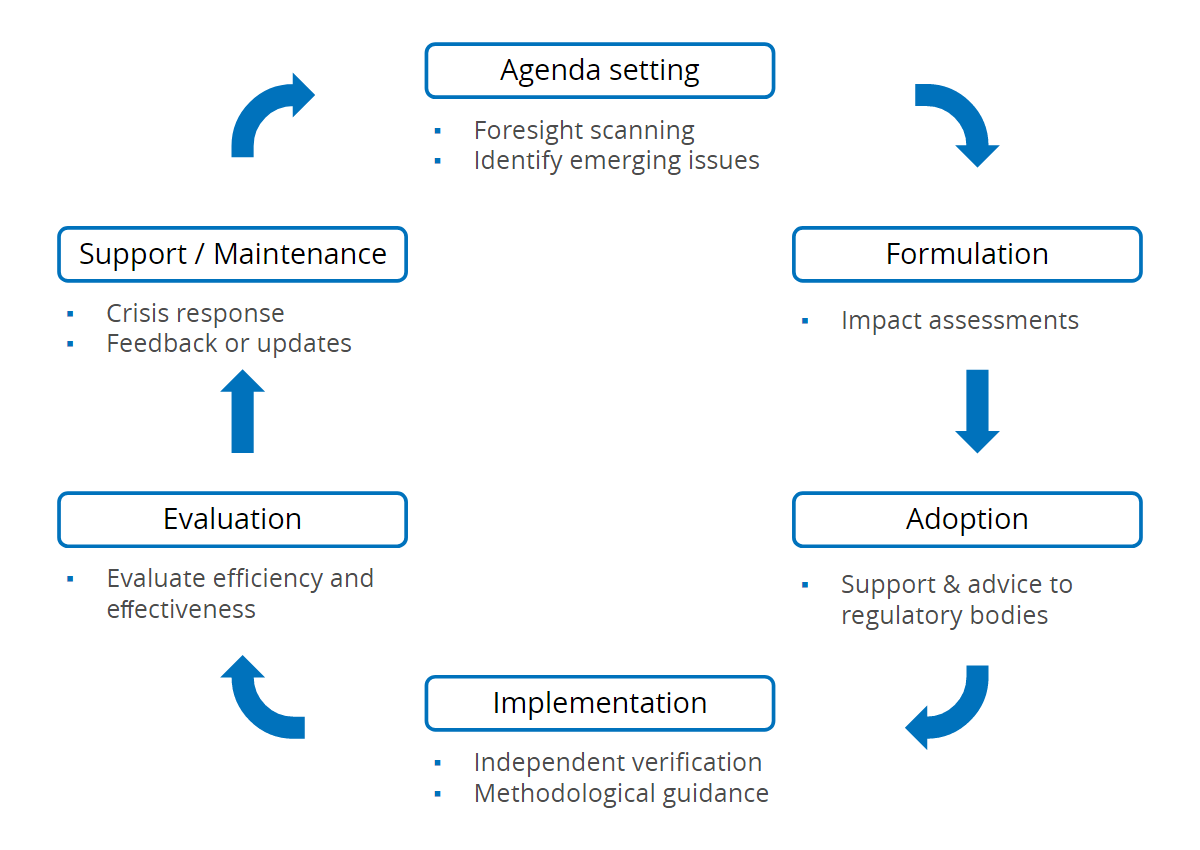

In academic terms, a policy cycle is an idealised process that explains how policy should be drafted, implemented, and assessed. A continuous flow such as the one below would provide structure and balance in the formation of any ongoing policy development and decision-making.

International student migration

When it comes to international education strategies, national study campaigns, and visa regulations, changes to policy can be a key competitive advantage – or disadvantage. In a world where education is quickly becoming more globalised, specialised, and competitive, many countries have developed international education strategies. This is to help their sectors become more adaptive, innovative, attractive, and internationally connected to respond to the opportunities and challenges that arise in the context of a growing pool of international students.

Strategies often differ in scope and specificity: the US is still in the process of defining a consistent strategy across all relevant government bodies. Canada and New Zealand, in their latest strategies, have moved away from a specific numeric goal and instead emphasize the diversification of international students and sustainable growth. France and Japan place a particular focus on offering more courses and degree programs in English, while Malaysia and China have stated their aim to improve the quality of their education systems to make them more attractive to international students. The UK in recent years has set out clear priorities for the recruitment of international students. Other countries such as Norway, the Netherlands, and Denmark have introduced policies that have been restrictive to international recruitment.

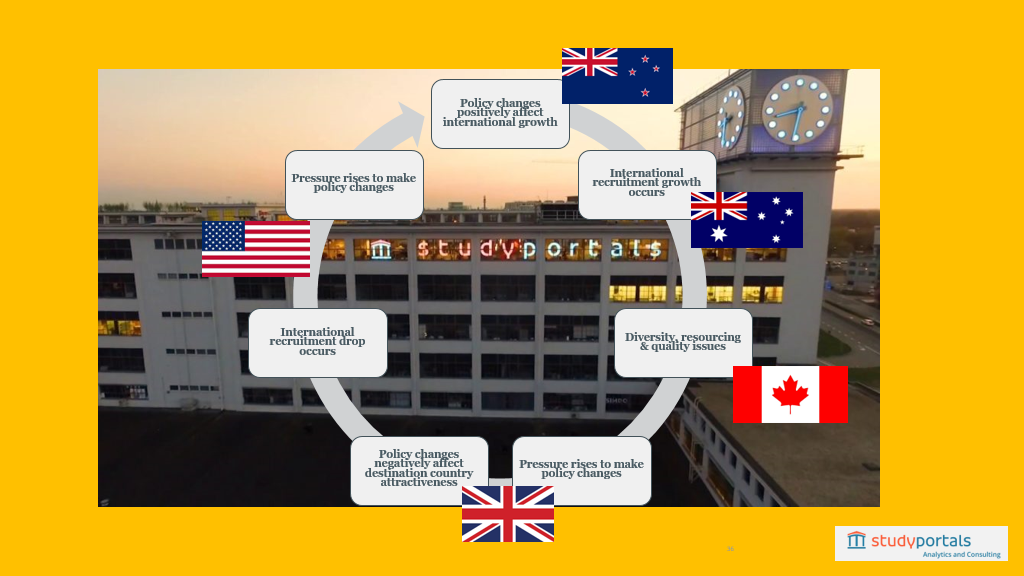

However, given that student mobility is often closely linked to migration figures, the idealistic policy cycle reference above can largely be replaced by the below continuous cycle which depends less on outcomes and more on economic and political pressures in the destination country. Whilst this cycle doesn’t seek to be an exact science, it gives an overall trend summary that has clearly played out across global study destinations in the 21st century.

Looking at the UK in particular, there is an increased pressure on the government leading up to the 2024 elections to show that they have, at least in theory, a control over migration figures. Leading figures across the sector have often called for student numbers to be removed from migration figures but to no avail thus far. The last time the UK made sweeping policy changes was in March 2011 which included the removal of a post-study work visa, the removal of the ability to bring dependents at the undergraduate level, and significant changes to the licences for institutions to be able to recruit international students. The knock-on effect of these changes on the competitiveness of international student recruitment compared to rival destination countries took the best part of a decade to reverse.

UK policy changes made in 2023/2024 are likely to have a similar, or worse effect for multiple reasons.

Domestically, the UK can no longer rely on the EU funding or student interest it enjoyed in 2011. Even for the home market, rising inflation figures combined with a fixed tuition fee mean that universities have lost around a third of their income since 2012. According to dataHE, this equates to almost £3 billion in losses from their annual UG teaching funding in just the past 18 months.

Additionally, as below, the rise in non-traditional study destinations as competitors in the market is significant and the options for students to choose alternative destinations with more attractive policies has grown and continues to grow at pace. A specific example of this- South Korea announced just last month that it had reached a new record number of incoming international students- and a significant percentage of these students were Vietnamese (23%)- which is also one of Sir Steve Smith’s top 5 priority countries in the UK’s international education strategy.

Current trends

The growth in the UK’s international student recruitment in recent years has been heralded internally in the sector, as the target of 600,000 international students was reached a decade sooner than aimed for. However, this growth was largely centred around PGT students from volatile markets that have been proven historically to be affected by migration rights and policy changes.

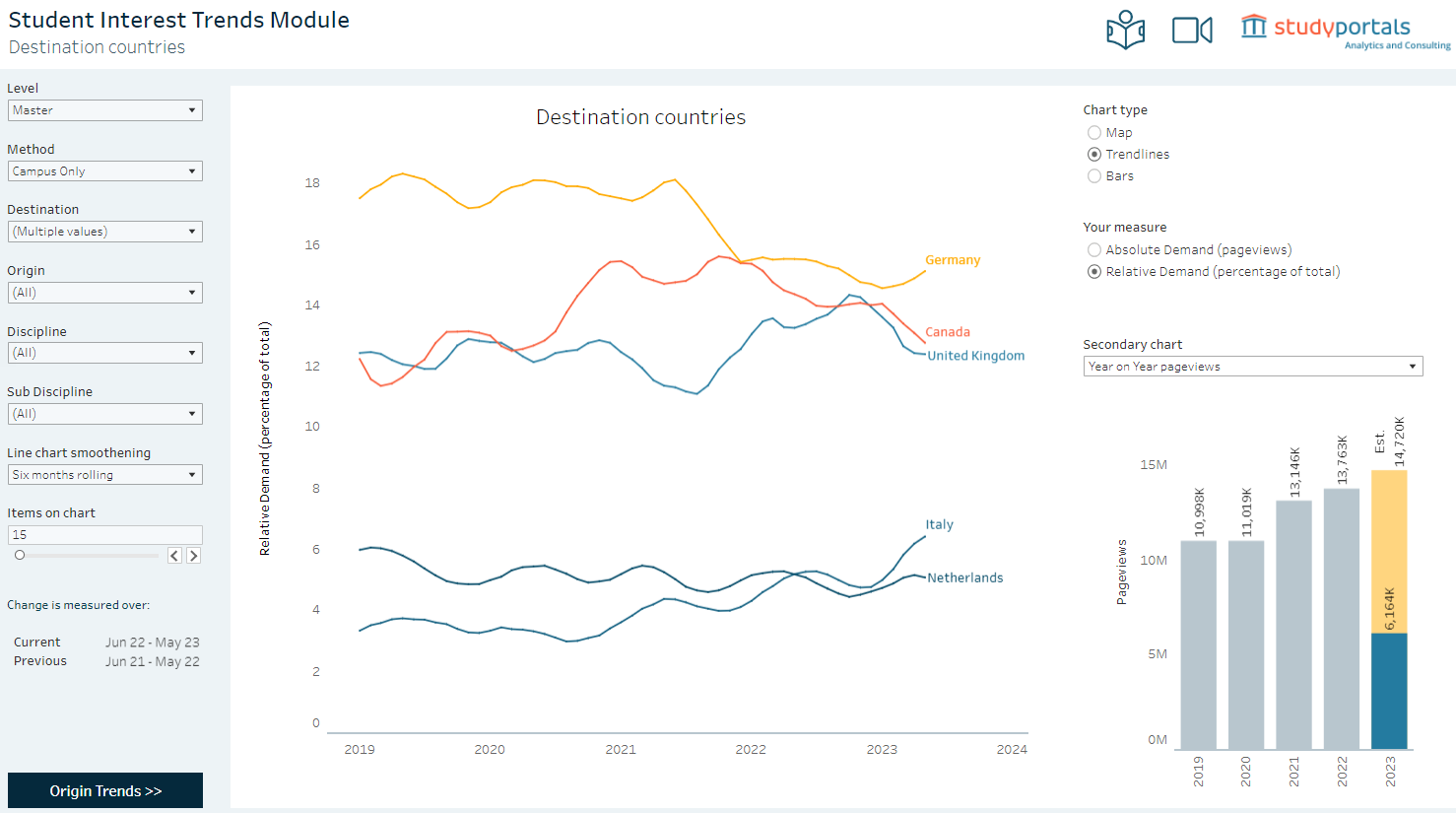

The below table shows that whilst the UK is still in a period of absolute growth in terms of student interest, in relative terms it is starting to lose ground for the first time as news of the upcoming change in regulations on dependents starts to filter through to markets.

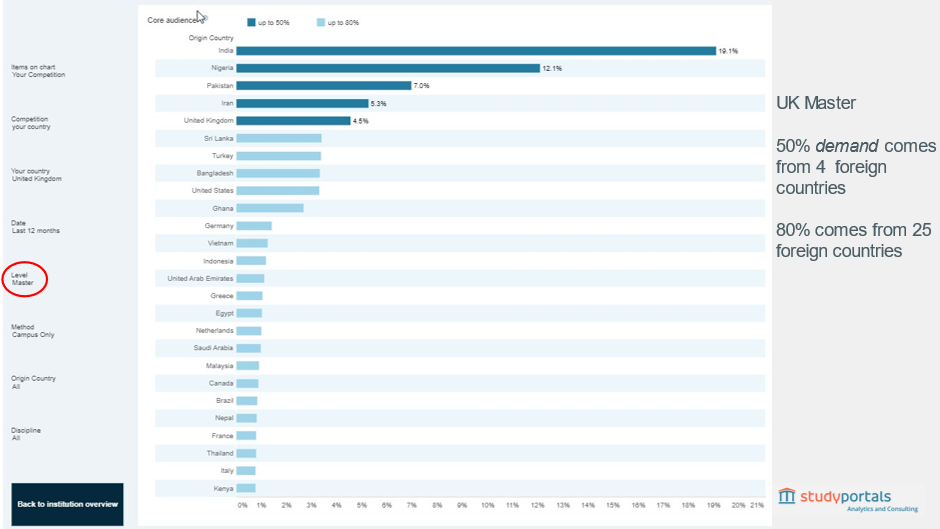

More worryingly, in the below chart we can see that demand for UK masters comes largely from 4 overseas countries, and 80% of its demand comes from only 25 countries- half as many as for the bachelor’s level. If these countries are made to feel unwelcome either in policy or by rhetoric it is likely to have a large adverse effect on incoming international student numbers in the UK, at a time when, as stated above, these students have never been more important to institutions across the country.

Action/mitigation

As pressure builds, it becomes very difficult to reverse through the cycle shown above. It will require both individual and collective action throughout the sector to mitigate changes made and the knock-on effect of the uncertainty it has on the student decision-making process.

Our previous article on this site explored individual ways universities can ensure their interests are spread across a variety of types and origins of students. In many ways, there’s never been an easier time to reach potential students globally and give them all the information they need to make an informed, best-fit decision.

To ensure a strong evidence base to lobby against policy change, institutions should also create a strong ethos of post-study career and visa support for international students. Perhaps most importantly, this support will assist international graduates to find the work they need and want and therefore keep a positive trajectory for stakeholders.

The most difficult trend to reverse in some sense is the potential rhetoric that international students in the UK don’t feel welcomed and wanted. There is a fine line between sensible policy and damaging sentiment. International students can bring a wealth of diversity, cultures, and experiences to our classrooms and their stories should be celebrated. The collective action of the formal relaunch of the #weareinternational campaign is a great example of this.

Conclusion

The comparison of policies relating to international students in the UK and its key competitors shows that overall, the UK currently provides an attractive environment for international students and its offer is broadly favorable over other study destinations.

However, the UK’s recent growth has largely been centred around markets that are likely to react negatively to upcoming changes. It’s vital for the sector that: a) UK policy does not further restrict international students and b) individual and collective action is taken by the sector to avoid negative rhetoric and make incoming students feel like the welcome, diverse positive assets that they are to our institutions.

Retention is likely to be a key priority into 2024. In order to retain the UK’s place as a top study destination, institutions will need to work harder than ever to retain students through the discover, application, and enrolment periods- then through their studies, and into their alumni networks. A strong, consistent message from both the UK Government and its Higher Education providers that international students are welcome is fundamental to keeping the sector on track.