Named on the Shaw Trust’s 2023 Disability Power 100, Atif Choudhury is a social entrepreneur with a background in economic justice and disability inclusion. Focusing on the inclusion of marginalised communities, Atif has worked on high-profile social development projects across the world, and spoken about his approach at global and national events. He is the Co-founder and CEO of Diversity and Ability and Zaytoun CiC (the world’s first Fairtrade Palestinian olive oil cooperative), Advisor to WHO Rapid Assistive Technologies Board, and trustee for Disability Rights UK.

As a brown man with dyslexia, I grew up believing that anything I thought that was different from my class friends was probably wrong.

Our education system- from early years through to further and higher education- often feels designed to welcome, accommodate, and celebrate only one type of learner. Growing up in Thamesmead (the UK’s second biggest council estate) as a second-generation Bangladeshi, I wasn’t that type of learner. For me, struggling to fit in with a different language and culture was enough to contend with. But my skin color was different from that of my peers, and that was a difference that couldn’t be hidden. Having to contend with a learning difference on top was too much. Rather than seeing the different perspectives, experiences, and thoughts I brought as bringing strength and innovation, my differences were a source of shame.

My journey isn’t a unique one; it’s a regular repercussion of our societal practice of separating identity into distinct ‘issues’. My journey reflects the repercussions of segregating identity into distinct ‘issues.’ Struggling to fit in with a different culture, I faced additional barriers due to my dyslexia. There wasn’t (and often still isn’t) an intersectional approach to inclusion in education. And the consequences of not being intersectionally inclusive can’t be understated, ranging from low self-esteem to loss of income, to criminal behaviour.

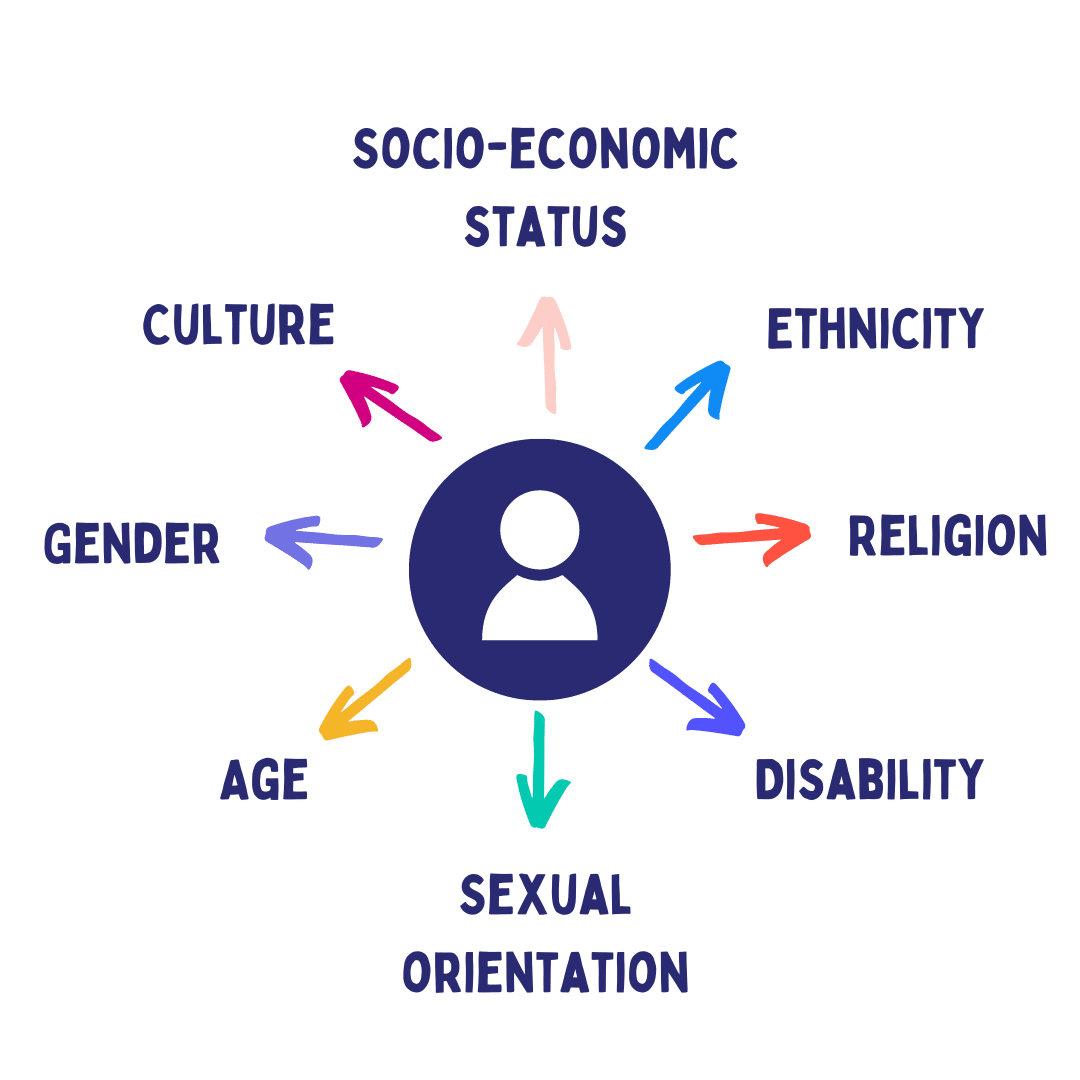

Intersectionality is not just another Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion buzzword. The phrase was coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw to explain how various elements of our identity intersect and influence our experiences and the chances we receive. Crenshaw highlighted how, as a Black woman, she encountered distinct obstacles that were not encountered by either white women or Black men, as the “intersectional experience surpasses the effects of racism and sexism individually.

Intersectionality recognises that our identities, including race, gender, disability, neurodiversity, and class, are interconnected and shape our experiences. In the context of higher education, a failure to embrace intersectionality perpetuates the siloed approach to identity-based exclusion. Often this means overlooking the profound impact of intersectional realities, like the intersection between immigration background, class, poverty, and race and how this impacts student life. An example of this is digital exclusion.

In education, it’s common to isolate aspects of identity into distinct ‘issues.’ Disability or Special Educational Needs (SEN) initiatives, alongside the UK Equality Act 2010, often dominate the discourse, inadvertently overlooking the intricate interplay of diverse identities. While legal frameworks like the Equality Act offer protection, compliance isn’t the same as inclusion and its focus on nine distinct characteristics does not consider the fact that a lot of people are more than one of the characteristics and that things, for example, a white disabled woman needs look different to what a Black disabled woman needs.

Furthermore, when our inclusion strategy is driven solely by adherence to the Equality Act, it places the onus on individuals to advocate for their basic access needs; this is a formidable task, given the historical denial of these needs.

Let’s investigate how this plays out in education:

Student C has always been told off for fidgeting, disrupting, and talking. Their behaviour is deemed so bad that eventually are put on a behaviour plan where it is then discussed seeking a diagnosis before granting some adjustments. This problematised adjustments so that now student C will always ask for them out of anxiety associated with performance and behaviour management. They are disclosing because they must, not because they want to share.

Flipping the way we approach adjustments, such as assistive technology, in education is a must for digital inclusion and intersectionality. At D&A we talk about an anticipatory welcome; that is, implementing inclusionary measures like adjustments without people needing to ask. This approach recognises that, because of intersectional barriers, people may not be able to ask for the adjustments they need. This could be because they’re overwhelmed by barriers, or because they feel they would be punished or they simply don’t know what is available. By providing assistive technology and support upfront education institutions can demonstrate that they understand this and are committed to enabling people intersectionally.

The pandemic laid bare the societal reliance on digital access, revealing a stark digital divide. Government initiatives providing devices must extend beyond hardware provision to address attitudinal and social barriers. An individual will face barriers even if they are provided with free tech if English isn’t their first language, if they have never had any digital literacy education, or if they have learning differences. In an intersectional understanding, we know that it is likely that they will face many of these barriers if not all. Therefore digital exclusion is not just a technological challenge; it is a symptom of an education system that fails to address the complex layers of identity. There must be enablers at every juncture to ensure that everyone can participate and assistive technology can encompass a great deal of these. Hence our journey towards inclusion necessitates the adoption of assistive technology as a key enabler. D&A’s approach involves personalised training, ensuring that technology reaches individuals and becomes an enabling tool.

Assistive technology is often misconstrued. People either think it’s inaccessible high-end software or that it’s adaptive software exclusively for disabled people. And yet people don’t realise that their worlds have been changed by assistive technology many times before. Texting was created as an assistive technology, as was Google Maps. If you look further back in time, I would even argue that glasses were originally conceptualised as assistive technology. Assistive technology can help, enable, and support everyone regardless of identity. It encompasses any technology, tool, or software that removes barriers, enabling a more efficient path or making life easier. From speech-to-text software to navigation tools and virtual assistants, assistive technology permeates various aspects of our daily lives. At Diversity and Ability, our team of disabled and neurodiverse people predominantly arrived at the organisation with a passion for increasing access to assistive technology, having witnessed the difference it made to their experiences in school, in further education, or the workplace.

A universal adoption of assistive technology seems a distant dream at the moment. It requires a fundamental shift in our understanding; one that dispels the notion that assistive technology is exclusively for disabled individuals. This broader perspective allows us to appreciate the diverse ways in which technology enhances everyone’s lives.

As we navigate towards a digitally inclusive future, the lessons learned during the pandemic underscore the need for intersectionality in shaping educational landscapes. We need to see inclusion not as a destination (or a specific SEN initiative), but as a journey that encompasses every part of our educational system and teaching practice. The goal is not only to make learning accessible for specific groups but to create an equitable, just, safe, and accessible environment for all. By prioritising intersectionality, we can bridge the digital divide and pave the way for a higher education system that truly values every individual.